“Making your mark on the world is hard. If it were easy, everybody would do it. But it’s not. It takes patience, it takes commitment and it comes with plenty of failure along the way.”

Barack Obama

There was something about the period between 2007–2009 that changed not just the world, but me. Certainly, the world order was upended in that interregnum between a legacy of war and the chaos that was to come, because the phenomenon known as Barack Obama transcended the world in which he was gaining acceptance, and stepped out into… THE WORLD. I cannot tell the precise moment when he was transfigured from a fixture of American news into the only human worthy of being quoted, but as a young man navigating my way through my third year of university, holding audiences spellbound with electrifying debates and pursuing a path of conscious leadership, Barack Obama was the way, the truth, and the life.

I recall that I raced to newsstands every morning to read excerpts of his latest speeches, that I spent valuable minutes at internet cafes downloading analyses and various commentaries comparing him with Cicero and Martin Luther King Jr, and that my most treasured possession was a square-faced wristwatch with Obama’s image emblazoned on the screen. I recall that the day when he was declared winner of the 2008 US elections, my dad called from the Caribbean to congratulate me and my lecturers cancelled classes for the rest of the day. Our worlds had changed in an instant. I knew that if I did anything exceptional in my life from that point, I could simply say that I was inspired by Barack Obama; I knew that it would be sufficient to say that Obama made me do it.

And so as I was transitioning into my final year of university in 2008, I felt a very strong internal urge to do something more impactful than the things that I had been able to do until that point. Many of the organizations in the university were focused on organizing public lectures, and campus politics did not much inspire me. There was little focus on developing leaders, supporting entrepreneurs or pursuing community impact. I did not see any organizations working to improve the learning conditions of students in under-resourced government schools, supporting children who were abandoned in orphanages or providing mentoring platforms where students could learn from young CEOs. That was a gap that I wanted to fill.

Over several months, I made notes in my journal about the organization that I would lead — how it would operate, the conferences that we would organize, the sectors in which we were going to function and the team that will drive it. All through my internship at the Lagos airport that summer, I snuck out my journal from under the table to add a few more ideas, and by the time I returned to campus for my final year, I had a very clear picture. I made a list of 10 people to whom I would introduce the idea — some were classmates, some were friends with whom I had worked on other projects, and one was a person whose work ethic I simply admired from a distance. I scheduled meetings with each one of them and explained the concept of this new organization to them — some asked several questions, some asked next to no questions; all were intrigued, and none rejected. On November 21, 2008, we launched The F.A.I.T.H. Initiative.

My team and I quickly designed projects that included a major annual leadership conference, an entrepreneurship competition (in collaboration with a US-based organization), an after-school tutoring programme at an under-funded government school and an orphanage outreach scheme. We established an in-house resource centre to upskill ourselves and even organized an event called “The Family Day Out”, bringing couples who had been married for varying lengths of time to share their experiences and balance out the negative stereotypes about balancing it all. On weekends, we would drive to orphanages where we donated several supplies and motivated the children; on weekdays, we would strategize about fundraising for our numerous projects. Within a few months, word had spread and several students came to ask if they could join the organization, and so we designed an application form and set up an interview process. It did not take long before we had to turn people away — we had far more applicants than we had work. After more than 100 volunteers had joined, we were oversubscribed.

In 2009, after I had won several public speaking competitions, people began to approach me asking me to teach them public speaking. My answer was “No, I do not teach public speaking”. After all, I had only gained competence by watching Barack Obama and Martin Luther King and reading just about every text analysis of their speeches, so I knew nothing about teaching. And of course, I had watched more than 20 TED talks, branched out into watching videos of Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, Les Brown and Tony Robbins. I had no interest in teaching public speaking, but I knew that I had started learning voice inflections, I had begun to master the power of a pause, and I definitely liked to dress in a black suit, white shirt and red tie, because…Obama! I must have turned away five would-be students until one fateful afternoon when a gentleman named Tosin Adeoye walked into my office and offered to pay me to become his private communications coach. I was stunned.

Nobody had ever attached monetary value to the knowledge that they believed I had. No one had ever expressed so much confidence in me. I knew that I did not have a curriculum to teach, but I had been challenged and I could not say no. That night, I put together ever resource available to me and started to develop my first public speaking curriculum. I taught Tosin privately for several months and then I took on a second client and then a third. I took on an offer to teach public speaking to senior secondary school students at a private school, and then junior secondary school. And then I added a second school. With growing demand, I advertised weekend classes at the university offering 40 hours of training over five weekends. We registered about 30 students for that first session, and my brother (and fellow public speaking enthusiast) became my co-tutor.

Before long, I had CEOs, corporate employees, pastors, engineers, university students, high school students and primary school students on my roster. By the time I incorporated The Speech Academy in 2010, my youngest student was seven years old and my oldest, I believe, was 70. I had brought on seven exceptional people onto the team and we were all being paid. We were living our wildest dreams, and I was running two organizations concurrently while undertaking a mandatory one-year national service in Nigeria.

On several occasions, when I have spoken about this period of my life, young people have asked a myriad of questions, so here are five lessons that I learned during that time:

1. Just start.

People always want to know how I found the courage to start an organization while in university, and how I aggregated the resources. My answer is simple — just start. When I started, I had no idea what was required to run an organization and I received advice from nobody. I simply wrote down my ideas in a journal, introduced those ideas to a few friends, invited them for a meeting and took their questions. The more questions they asked, the more I refined the idea. We had no funding, no registration documents, no advisors — nothing. All we had was passion and that was enough. The rest came after.

2. Find people whose abilities complement yours.

In other words, find people who are smarter than you are. The people whom I invited to work in both of my organizations were very impressive. They were brilliant. They were resourceful. Each of them could have established their own organizations, and nearly all of them have gone on to do exactly that. They were the ones who developed and implemented our projects; they were the ones who used their networks for fundraising; and they were the ones who invited guests to our events. They were the ones who donated their scholarship funds to help build our organization; they were the ones who brought in other exceptional people to the team; and they were the ones who motivated me to keep going on the days when I was not sure that I knew what I was doing.

3. Find opportunities to create value.

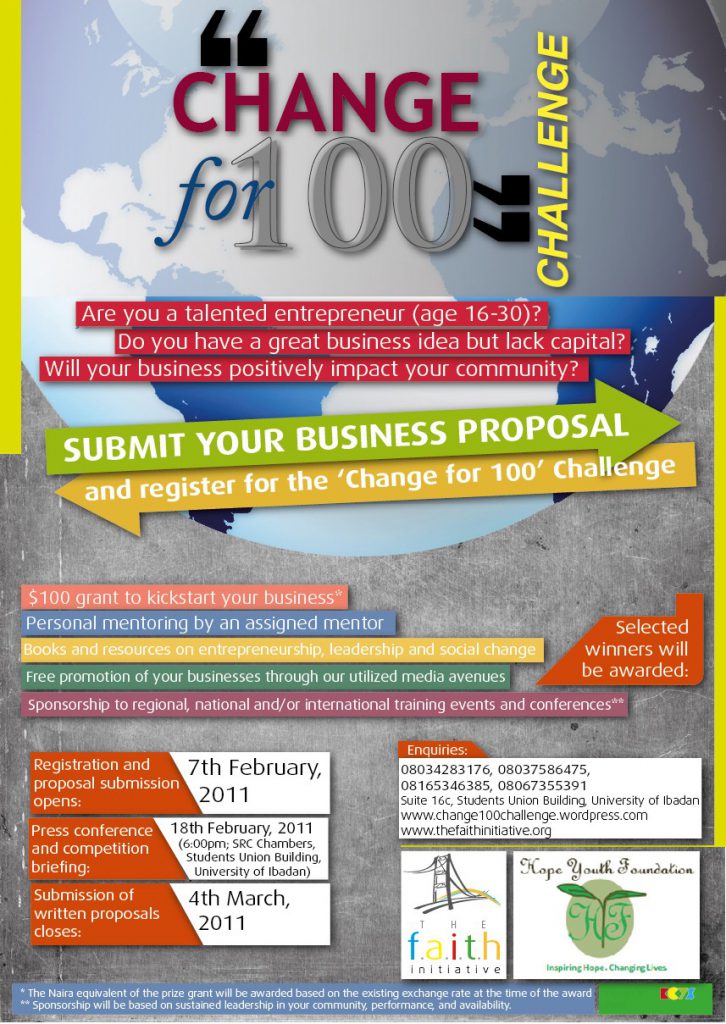

In 2009, we introduced a project called Change for 100, in collaboration with a friend of ours, Simi Lawoyin and her organization, Hope Youth Foundation. The premise was simple — if you had $100 to design a project to significantly improve the lives of people (say 50 people) around you, what will you create? So many people think that they cannot do anything with such little money, but my experience shows that if you cannot do it with little, then you cannot do it with much. That year, we had several entries and four people earned the prize money to create those projects. That same year, I led my team to record a video documentary about the abject state of Abadina College — the government-owned school where we were organizing after-school classes — and we kicked off a fundraising project to help rebuild the school. We purchased mathematical sets and booklets of formula tables for all final year student in the school, in preparation for their examinations. That same year, we volunteered on Saturdays at different orphanages and donated supplies worth more than N100,000. And then we organized a food distribution drive to one of the poorest parts of the city and gave out about 100 packs of food to celebrate the birthday of one of our members. There are several ways to create value, and we were busy exploring them.

4. Set high targets and work hard to attain them.

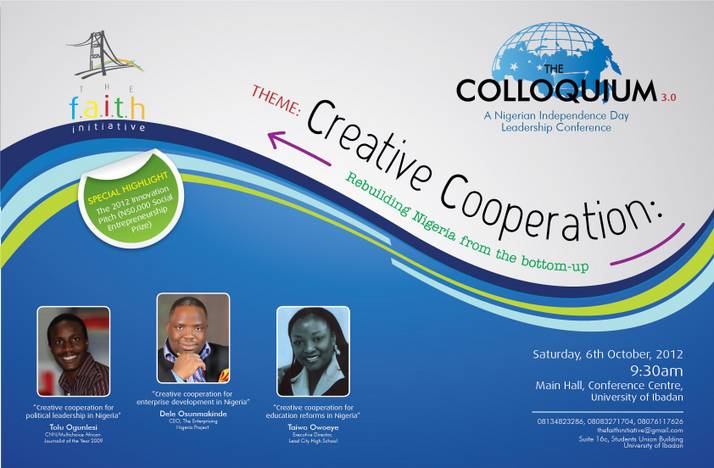

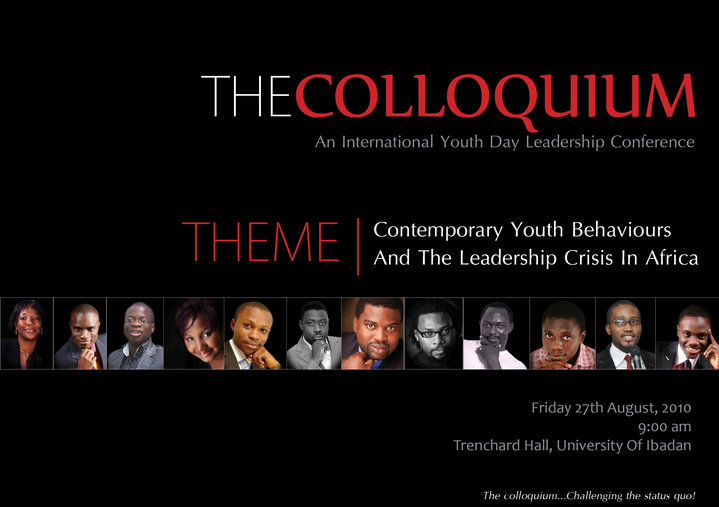

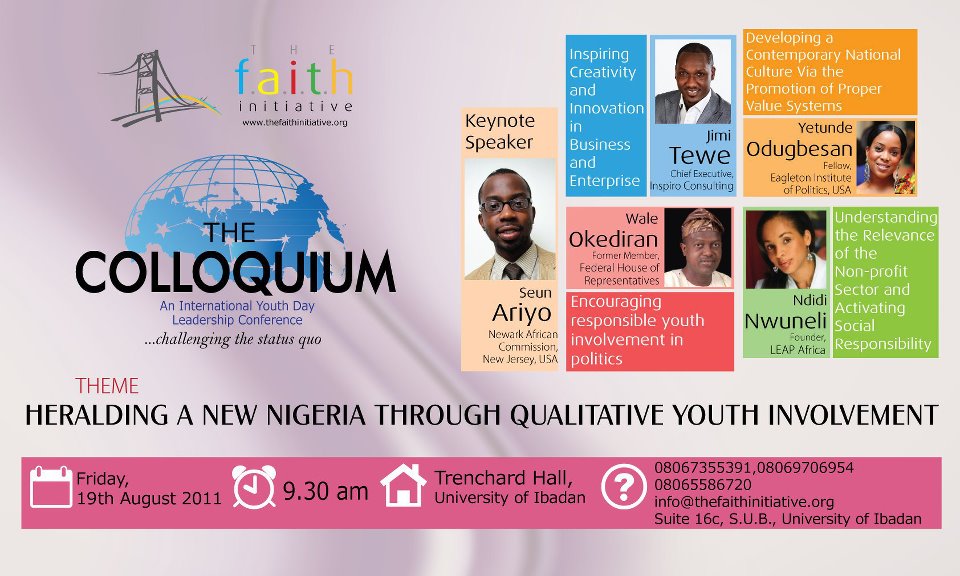

When we introduced The Colloquium, our annual leadership conference in the University of Ibadan in 2010, I had no idea what it would require, but I was determined to try. We paid N90,000 for the biggest hall in the university, we rented more than 500 chairs, and we invited some of the most inspiring speakers in the country. We printed posters and brochures, paid for lunch for the entire group and recorded advertising jingles. We even bought a cake to officially launch the organization in public. That conference and the two subsequent ones were very successful. After that, my team truly believed that they could do anything.

5. Make people pay you for your services.

In 2009, I was absolutely in love with public speaking, but I had never considered teaching it until I got offered money to do it. It was a very important lesson for me. Perhaps the reason that I had not moved quicker was that no one had attached a value to my services. It took me a while to know how to demand a proper rate for my speeches, and I felt so shy the first time I was asked how much I would charge for a 40-minute speech. When I moved from teaching at the first private school to the second, I had multiplied my rate by five times. Don’t be afraid to ask for your work to be valued. You deserve it.

I have not yet met Barack Obama, but I cannot wait to tell him one day how much of a difference he made in my life. I know that he will love to hear it. Between now and then, I will continue to make the same difference in the lives of other people. That is a worthwhile investment.