In July 2010, I travelled to the farthest place on earth that I have ever reached: I was in the north-western region of Russia, just off the lake Seliger in the Tver region. I had been invited to attend the International Youth Forum convened by the Federal Agency on Youth Affairs of the Russian Federation, alongside a few thousand young people from all over the world. I had secured this opportunity after winning an inter-university debate in Nigeria in 2009. Russia was the first place where I recall experiencing discrimination — all the way from the airport where I was kept on hold for two long hours while my passport was scrutinized, through the city of Moscow, and in public parks. But in Russia, I also experienced something else — inspiration.

At the Forum, I felt very small and anonymous in a sea of changemakers from all corners of the world. I sat with them at lunch, listened to their stories, engaged in workshops with them, and lost myself in imagination of what life could look like in a completely different part of the world. I was surrounded by exceptional people from as far off as Uzbekistan, Colombia, India and other countries that I had only heard of in the media, and I knew that I did not want to return to Nigeria to continue the same static life in which I had been raised. I had experienced something that caused a shift in my mind — a concept best captured in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave — that when you have been stuck in a particular way of life for so long, you tend to perceive that way of life as normal, until you are exposed to a completely different reality.

I returned to Nigeria a different person — that summer, I started applying to graduate schools in the USA for a Master’s degree, knowing fully well that I could not afford it and I had no relatives there. I was passionate about International Relations; I also wanted to learn how businesses and governments intersect to create a fully functional society. Above all, I was keen to study the world of international NGOs, hoping to find a program through which I could learn to transform the organization that I had founded two years prior into a world-leading organization. I applied to four graduate schools and had the good fortune of receiving an offer of admission with a generous scholarship from the top-ranked university specializing in the study of Public Administration — Syracuse University. I could not have been more excited.

Except that there was just one tiny problem. I still did not have enough money. All the savings that I had accrued from my business, my speaking engagements and from my family was just over $1000, but I left for New York anyway. A very kind family took me in for the first week before I made the trip upstate to Syracuse where another angel generously helped me settle in and did more for me than I could ever have asked. Within two months, money ran out, but I never lacked help. My meals were almost always potatoes, noodles and bread, and whenever I was feeling particularly buoyant, I would order two slices of Pepperoni Pizza and a can of Pepsi for $1.50. I attended a handful of campus events where snacks were available and I drank from the water fountains in the hallways. All the while, I pushed myself academically in a very rigorous program, knowing that I was not cut from the same academic cloth as some of my classmates. I was the only African in my class and I somehow overcame that discomfort and continued to seek opportunities for growth.

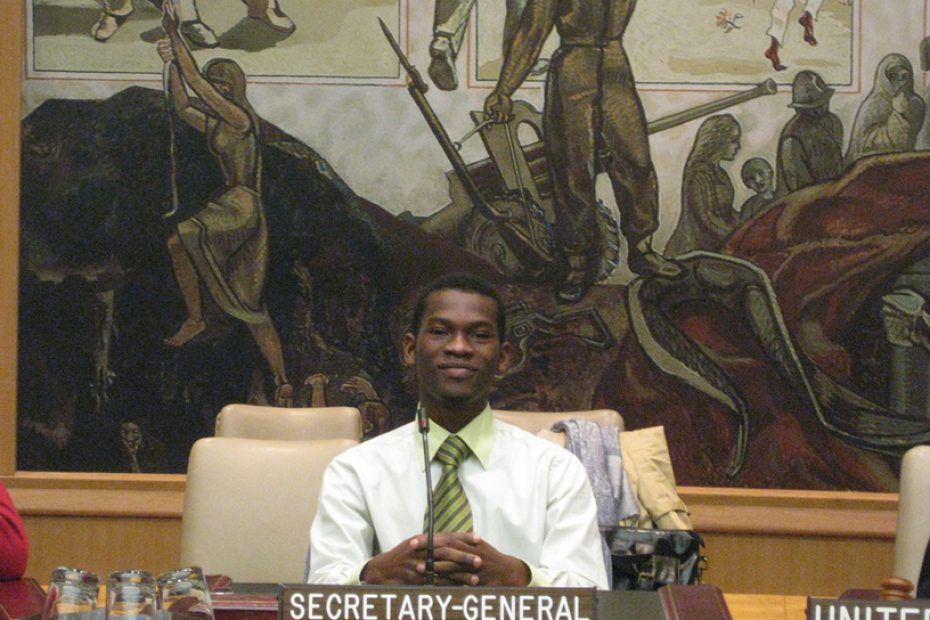

As I had done during my undergraduate days, I threw myself into opportunities in Syracuse, even when it was not apparent that I was qualified for them. I put myself forward for the position of President of the Coalition of Multicultural Public Affairs Students (COMPAS), and I was elected. I nominated myself to serve as the graduate students’ representative on the University Senate, and I was surprised to find myself in a committee reviewing prospective recipients of honorary doctorate degrees. I took a class in Humanitarian Action and found myself on a trip to the United Nations where I stood behind the same podium from which world leaders deliver speeches (I caught a glimpse of my future). I led my organization, COMPAS, to teach International Relations voluntarily to middle school students; I served as leader of a team of consultants for a non-profit organization and helped them develop their first strategic plan. I travelled severally to New York, New Jersey and Philadelphia to deliver speeches at conferences; I moderated a panel at the American Society for Public Administration; and I attended the International Development Conference at Harvard.

And then I joined Toastmasters International — I loved my local club, Orange Orators, and I looked forward to our weekly Tuesday meetings. I jumped in hard and achieved the Competent Communicator and Competent Leader certifications probably quicker than anyone had ever done. I delivered weekly speeches, served in leadership roles and won three international public speaking competitions. I was on course to participate at the World Championship of Public Speaking, except that the state championship conflicted with my final examinations. I became a columnist for a top publication in New York and concurrently wrote for another news analysis organization in Nigeria. I did all these things and many more while running my NGO remotely in Nigeria and completing four semesters of a Master’s degree in 12 months. I was a man on a mission.

In 2012, while many of my classmates were heading to Washington, DC for jobs at the World Bank and other international organizations, I received a call from another country that I had never visited — South Africa. I was offered a visiting faculty role to help develop a curriculum in communications for an institution that had a clear mission — to transform Africa by identifying, developing and connecting its future leaders. I said yes, and left within days for Johannesburg with nothing more than a suitcase. Within a month of arriving at African Leadership Academy, I had helped to kick-start the first phase of curriculum development and I had taken on a whole different project — creating a platform to develop future public sector leaders for Africa. I began to mobilize resources to enable eight students travel to the Harvard Model United Nations conference in January 2013 and the Georgetown Model United Nations in Qatar the following month.

It was around that time that the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) first reached out to me to begin to provide international commentary for them. I loved the times that I was interviewed by the great Komla Dumor, particularly during Barack Obama’s visit to South Africa in 2013 and after Nelson Mandela’s death. While teaching Writing & Rhetoric full time during the week, I taught International Relations on weekends, and I planned conferences in between. In 2013, I started planning the inaugural Model African Union conference, which would draw about 80 participants from around Africa and beyond. In the succeeding seven years, I worked with more than 400 young leaders to organize the conferences, hosted more than 1,500 participants and managed a combined budget in excess of $1million. Within six years at the Academy, I had gone from a Fellow (entry level) to the Executive team. I had finally arrived in position to understand how to manage a top international organization, as I had envisioned on my return from Russia in 2010.

As I look back on the last decade, there are five principles that have guided me and continue to guide me today:

1. Excellence is a culture

One of the most destructive habits that I have found in young people is that we have been conditioned to complain more than we innovate, and we tend to identify every reason why an idea will not work before we have even made an attempt. We have the opportunity to shift our minds away from a pattern of perpetual complaints and focus instead on making the most of our opportunities. Excellence is a culture — a collection of habits that become a pattern. The mindset with which we approach academic endeavours will be the same mindset with which we approach relationships, jobs and everything else. Decide in your heart that things will be done to the best of your ability and then give them your best effort.

2. Be aware of your limitations and be thankful for your opportunities

At African Leadership Academy, I encountered a definition for humility that I had never heard before. It read: “We are aware of our limitations and thankful for our opportunities”. For some reason, I had been conditioned to believe that humility was all about having a quiet demeanour; I did not realize that it was possible to be confident and outspoken, yet humble. If you choose to recognize that everything you have is a blessing and if you practice gratitude for those things, while recognizing that you are probably not the smartest or most gifted person on earth, then you will truly go far in life.

3. Hard work never kills. Laziness does.

This was perhaps my mum’s favourite saying when I was growing up, and I did not like to hear it, because she often invoked it when reprimanding my siblings or me for being late on our chores. However, I have come to realize that she was absolutely right. As hard as I work, I remain energized. I continue to find new ways of pushing the boundaries in everything that I do, and God crowns my efforts with success. The one non-renewable resource that we all have is time. Each day that we live, we are drawing down on our total. If we spend our days contributing value to the world, we would have lived truly fulfilling lives when it is all over.

4. Be resourceful in all environments

I have discovered that I will not always have all the needed resources at my disposal, and I will not always be the smartest person in the room, but I need to find a way through the platforms available to me to create value. Each of us must ask ourselves, regardless of our circumstances, “What value can I create? Whose life can I improve? How can I help?” It is a shift from approaching life as though someone owes us something to realizing that it is up to us to leave each environment better than it was when we arrived.

On the walls of the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs where I studied, I found these words engraved from the Oath of the Athenian City-State:

“We will ever strive for the ideals and sacred things of the city. Both alone and with many: we will unceasingly seek to quicken the sense of public duty. We will revere and obey the city’s laws: we will transmit this city, not only not less, but greater, better and more beautiful than it was transmitted to us”.

Oath of the Athenian City-State

5. Everything will make sense down the line

On the last day of the International Youth Forum — Seliger 2010, I felt a deep sense of emptiness as I walked around the expansive campsite watching crew workers tear the place down. For 10 days, I had lived in a bubble and it was time to return to my reality, but nothing felt the same in my mind. I did not immediately notice the tears that had welled up in my eyes, but I was keenly aware that I felt an obligation to do more with my life. When I returned to Moscow, I did not much mind the piercing stares from people in the city as I wandered around the Kremlin, observed the eternal flame in the middle of Red Square, and read the inscription on Lenin’s Mausoleum. I was a little disgusted by the insolence of the little kid in the park who grabbed tightly to his mum and pointed at me as I walked past, but I was wrapped up in my own thoughts. Russia was the backdrop to the internal jostling that I experienced — “will my life amount to much? Will I know exactly what next steps to take? Will I build a truly international community? Will I make any tangible difference in the world?” Those thoughts plagued me all the way from Sheremetyevo International Airport to Istanbul and finally Lagos.

I have come to realize that our lives become the totality of the individual actions that we take — that we are better off previewing our futures through the actions of today. If our works are not credit-worthy today, they will not be tomorrow; but if we commit to creating value, even if we do not see the results immediately, everything will make sense down the line.