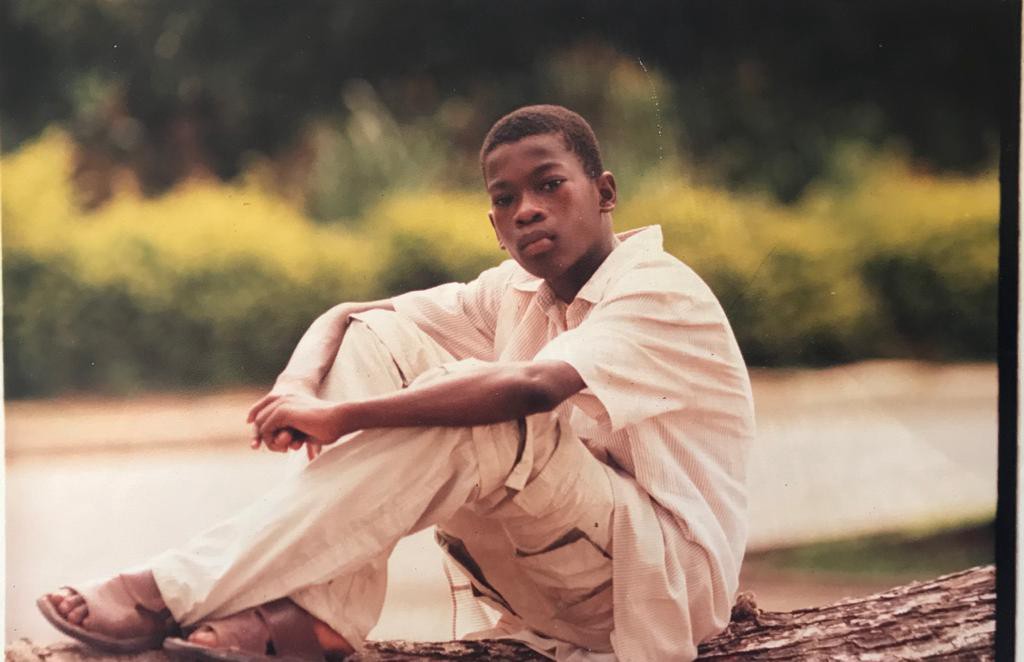

When I was in high school, I must admit, I was not at the top of my class. There were many more students who came from better-resourced families, and whose academic achievements mirrored their privilege. I did not have all the textbooks that I needed, the encyclopaedias, the extra lessons, the summer schools, and all those other factors that play a huge role in a person’s emergence, especially in their formative years. The closest I came to receiving an academic prize was coming in 4th place in one subject. When I wrote the University Matriculation Examination in 2004, I scored 230 out of 400. While I did not start my journey as an academically exceptional student, I was working hard nonetheless. The turning point arrived in the transition from high school to university.

Nigeria is notorious for having untold disruptions to academic calendars. Due to the nature of incessant strike actions by universities, I had to take an unintended gap year after securing university admission. That year changed everything for me. I saw some of my classmates proceed to stable private universities while others went abroad. I did not have those privileges. Instead, I took a job as a photocopier at a business centre in the University of Ibadan. My job was to make copies of past examination questions, class notes and other learning materials for students in the Faculty of Science. There was another gentleman who had been employed there before me — he was the typist on the desktop computer. The owners of the business were teachers who conducted statistical analysis for Master’s and PhD students using the SPSS software.

Each day, as I made photocopies, I began to observe the dexterous finger movements of my advanced colleague on the computer, and I assisted with coding questionnaires and data entry into SPSS. On weekends, I would practice typing on the computer when no one was present, and promptly return to the photocopy machine on Monday. After a few months, the typist left and I made a pitch to the business owners to be promoted to the computer. Because I had taught myself to type on weekends, I earned my first promotion at the age of 16. After nine months, I had perfected my typing and learned the rudiments of statistical analysis. I was ready for university.

More importantly, I had spent those nine months observing students across the Faculties of Science, Engineering and College of Medicine who took classes in the huge lecture theatre where the business centre was located. I saw them wearing brilliant white lab coats; I saw them doing assignments together; I saw them running study group sessions; and I saw them sit for examinations. There was something about the way they carried themselves that appealed to me. They were the cream of the crop and I desperately wanted to be like them. That same year, I made a commitment to read books as though my life depended on it. I began to write down the titles of books that I read. My target was to read 100 books before December. By august, I had reached my target.

So, here are five lessons that I learned from that period in my life:

1. There are no disadvantaged people.

I am convinced that there are no disadvantaged people in life. There are only people who refuse to make the most of the resources available to them. I know that there are people who have had it far worse than I have in life, but I have also seen people from much poorer backgrounds who have achieved far more than I have. We need to stop complaining about what we do not have and start maximizing what we do have.

2. There is always a reasonable alternative to your first choice plan.

If you cannot go to school at the time that you prefer, find a job. No matter what you do, make sure that you are learning something. The one year that I spent working as a photocopy operator and a typist was one of the most defining years for me. I learned to be diligent, resourceful, organized, respectful and professional. I developed skills. I made connections. I envisioned my future. That year was supposed to be a waste, but it turned out to be one of the greatest blessings of my life.

3. Read as though your life depends on it.

You have definitely heard this several times, but it perhaps has not fully registered in your consciousness. You cannot change what you do not understand. If you want to change the world, you have an obligation to learn as much as you can about it. During my gap year, I read books on every topic that I could find. I read newspapers. I read magazines. I read small pamphlets. I read big Bibles. There were no ubiquitous mobile phones at that time; I did not have internet access; I did not have a laptop computer — all of those things are present today. Through reading, I improved my vocabulary, I transformed my perspectives and I developed new ideas.

4. Embrace opportunities even when they are not presented to you.

Four years before my gap year, I had done something radical. In between junior high school (middle school for Americans) and senior high school, I had a four month holiday. I asked my dad for permission to learn a trade. At the age of 13, I took an apprenticeship to be a photographer. My dad made a connection with a photographer who lives in a town about an hour and half from where we lived. I lived alone during the week, and my parents came into town on weekends. I would get up every morning, make my breakfast, take the taxi to work and stay until late in the evening. Each day, I watched my boss take passport photographs, develop them in the dark room and then print them out on photo paper. I would do the honours of cutting them into the appropriate sizes. When I was 16, I was working as a photocopy operator and the a typist, and I was also learning statistical analysis by observation and participation. Four years after, when my classmates were paying specialists to design and analyse their questionnaires for their final year theses, I did it all by myself. I saved money. No one had given me permission to learn those things. I just did.

5. Practice what you observe other successful people doing. You just might get similar results.

When I eventually enrolled in university, one of the first things that I did was what I had seen other students doing when I was a photocopy operator in the back of the lecture theatre — I formed a study group with three of my classmates. I realized that being able to discuss the content that we all learned in class was a good way for me to firm up my understanding of those concepts. It was not enough for me to take notes in class or read lecture notes — I learned best by discussing in a group. Eventually, I would combine notes for textbooks, the Microsoft Encarta Encyclopaedia (the precursor to the internet for those of us who came of age in the late ’90s and early 2000s), and from those group discussions to form my own notes. That was how I became an A student.

What is missing from the story of this episode in my life was that I did more than one menial job as a student. I spent one of my holidays on a farm with my family, harvesting cassava for sale — this was how we paid my tuition for my second year of university. The other holiday, I spent partly washing buildings at a construction site. I also took on a job as a part-time Geography teacher at a newly formed secondary school, and I became an after-school tutor to a high school student in my neighbourhood. And so when people ask me today why I work so hard, I always resist the urge to ask them: “Have you ever sold cassava to pay your tuition?”