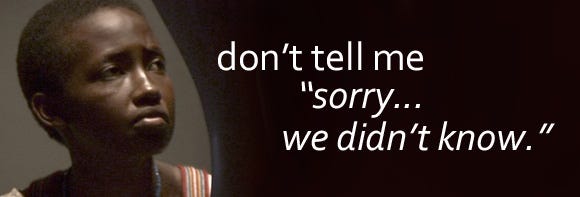

My legs were failing me as I stood in front of the wall in this slightly darkened alleyway, deep in the heart of the Kigali Genocide Memorial. Story after story gripped my heart and all my strength seemed to drip slowly away from me. This was an atrocity beyond proportions, and one from which the world will never recover. How did humanity descend so low? How could we have allowed this to happen? As people flocked by taking photos and shaking their heads in disbelief, I couldn’t bring myself to move away from this one poster on the wall. It told the story of how nearly a century before the cataclysmic massacre of an estimated 1 million people in 100 days, the white man (in this case, Belgians) had attempted to establish a class structure of Rwandan citizens based on their own understanding.

The world now knows the story of what happened in Rwanda in 1994, but it is important to take a step back into the invasion and colonization of Rwanda by first the Germans, then the Belgians after World War 1. Capitalizing on the fact that Hutus were predominantly farmers while Tutsis were predominantly cattle herders, the colonialists sought to legally position the Tutsis as the more intelligent group apparently because cattle herding seemed to be a more noble and rewarding endeavour than crop farming. Such simplistic thinking led the colonialists to further analyse the skull size (again, the size of the brain was apparently equivalent to increased intelligence) and skin colour and conclude that the Tutsi must have Caucasian heritage, and were thus more intelligent than the Hutus.

It is completely ridiculous to think that the white man with all his perceived wisdom could have been so foolish. That era of ‘superior thinking’ from Africa’s colonialists has birthed several generations of timid Africans who have not recovered from the flawed perception that the skin colour and heritage of the white man makes him inherently more intelligent. In any case, the damage was done; Rwanda was divided for good. The Tutsi received better education, better support and higher political positions in the country. Even in the Catholic Church, the Tutsi were favoured for leadership positions. A seemingly harmless attempt by the white man to ‘help’ poor Africans led eventually to the deep ethnic segregation of peaceful neighbours and the eventual darkening of the clouds over the land of a thousand hills.

I was starting to recover from my recent trip to the Genocide Memorial and my disgust for the insolence of the German and Belgian colonialists when my social media timeline was flooded with vituperations about yet another white saviour. I have never allowed myself to get drawn into social media wars, but I could not let go of this one.

Why, oh why, do people with seemingly good intentions perpetrate such foolishness and leave the whole world palpitating with uncontrollable anger?

Why did Louise Linton decide in 2016 to publish an ill-conceived memoir about her journey as an 18-year old to “Africa” (as though 54 countries weren’t diverse enough) in 1999? Surely, 17 years is enough time for her understanding of the world to have evolved to enable her tell a balanced story? But no, she simply had to explain how she, a former pupil of a “prestigious” college in Scotland had gone “to Africa with hopes of helping some of the world’s poorest people”. Seriously? What was she thinking? Which privileged 18-year old on their first trip to “Africa” could save the world’s poor by straddling them on their laps and feeding them a bottle of coke?

Louise Linton was incredibly reckless with her memoir, and she deserves all the criticism that her book will get. In attempting to justify herself, she wrote on Twitter that “I wrote with the hope of conveying my deep humility, respect and appreciation for the people of Zambia…” No, you did not! You disparaged, belittled and disrespected Zambia. You perpetuated the exact same stereotypes of Zambia and the rest of Africa that little white saviours like you have publicized over many generations. Who would have read Louise’s book or the extract published in The Telegraph and said: “Oh, how wonderful those Zambians are!” That book was written to elicit cheap pity and it is a sorry attempt at telling a good story. Louise should be terribly ashamed of herself.

As I attempt to shake myself off and spray some positivity on my day, I am reminded of exactly what I typed on my phone in that moment within the heart of the Genocide Memorial: “It is possible to do a lot of evil with good intentions. The colonialists brought education and religion to Rwanda, but sadly also created huge divisions in the country be classifying people based on race, skin colour and perceived intellectual capacity. What a shame!” Perhaps this will be a good time for the world to adopt the 4-way test of the things we think, say and do, popularized by Rotary International:

1. Is it the truth?

2. Is it fair to all concerned?

3. Will it build goodwill and better friendships?

4. Will it be beneficial to all concerned?

I’m very sure that Louise would have decided against publishing that memoir, had she subjected it to the simple scrutiny of the questions above. I look forward to reading her detailed apology.